"Try Wait"

- Ocean Hoptimism

- Dec 17, 2025

- 4 min read

What Happens When a Community Hits Pause on Fishing and the Reef Responds?

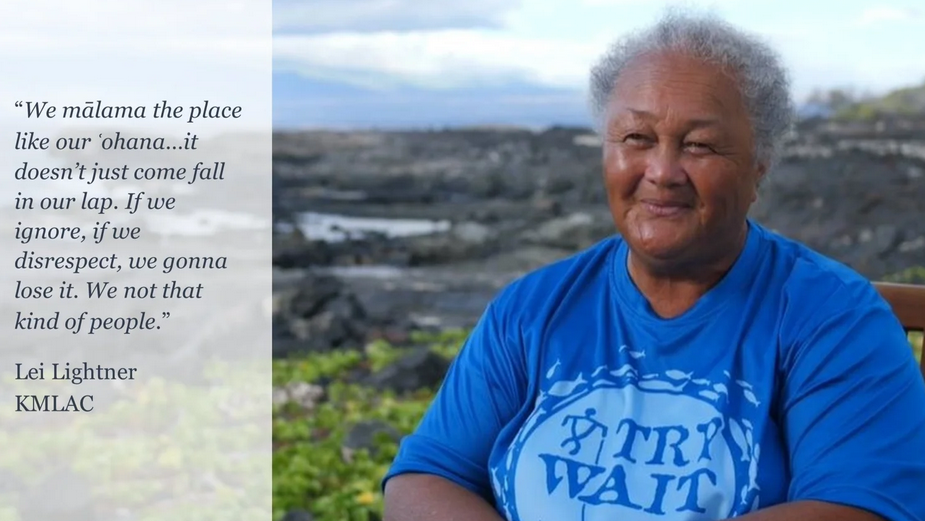

Some solutions don’t arrive with a policy announcement or a global summit. Sometimes they begin with a quiet, culturally rooted reminder: “Try wait”—a Hawaiian Pidgin phrase meaning, simply, pause and give things time.

In 2016, along the west coast of Hawaiʻi Island, the community of Kaʻūpūlehu made a decision that would ripple far beyond the tide line. Faced with declining fish abundance, changing ocean pressures, and the loss of the generational certainty that the reef would always provide, community leaders, fishers, kupuna (elders), and cultural practitioners decided to stop fishing for ten years. Not out of resignation — but out of care.

Rather than asking, How much can we take? they asked, What does the reef need to recover?

A Rest Based in Relationship

Kaʻūpūlehu’s reef was never just a food source. It was identity, practice, childhood memory, weekend rhythm, and ancestral inheritance. Fish like uhu (parrotfish), kala (unicornfish), and weke (goatfish) once filled nets and dinner tables. Over time, though, the story began to shift. Larger fish became harder to find. People traveled farther for the same catch. What had once felt abundant began to feel uncertain.

That kind of ecological change doesn’t scream. It whispers—through empty habitat, through long hours at sea, through the uneasy knowledge that something foundational is slipping.

So the community chose rest, guided by the Hawaiian stewardship principle of kapu: temporary restriction as a path toward renewal. In partnership with Hawaiʻi’s Department of Land and Natural Resources, the community formally established a nearshore no-take area extending from the shoreline out to a depth of about 120 feet, covering roughly 3.6 miles of coastline. And then the hardest part began:

They waited.

What Happens When We Leave the Ocean Alone?

For the first few years, skeptics weren’t hard to find. Some wondered whether pausing fishing would make a noticeable difference. Others argued that modern stressors—warming seas, pollution, coastal development—were too overwhelming for a community-led closure to matter. Still others voiced concerns that a ten-year closure was too long.

But ecosystems have long memories and extraordinary stubbornness. Give life a chance, and often it will take it.

Two years into the ten-year ban on near shore fishing at Kaʻūpūlehu, surveys began to show certain fish populations were rebounding. Within six years, researchers from The Nature Conservancy monitoring Kaʻūpūlehu reported something remarkable: fish were coming back—and not just in number, but in size and diversity. Species prized for food, especially well-traveled adults capable of producing large numbers of offspring (the BOFFFF concept), were once again part of the reef’s daily story. The abundance inside the protected area grew dramatically, while nearby fished areas saw almost no change. The closure wasn’t theoretical. It was working.

Kaʻūpūlehu had become a living experiment in resilience, and the ocean responded with evidence.

2026: A Turning Point, Not a Finish Line

Now, the ten-year commitment is nearing its planned transition point. The agreement didn’t promise that fishing would automatically resume when the calendar reached 2026; it promised something far more thoughtful. Fishing may return only when a community-driven, culturally grounded fisheries management plan is finalized and approved by the state.

That plan, still undergoing process and review, reflects a shift from extraction toward stewardship. Instead of asking whether fishing will return, the community is asking how it can return responsibly: through size protections, seasonal consideration of spawning periods, and ongoing monitoring grounded in both science and cultural practice.

The next chapter is not about going back. It’s about going forward differently.

Recovery Is Not the End of Responsibility

It’s tempting to see the return of fish as a happy ending—evidence that the ocean is healing and can now be reopened. But Kaʻūpūlehu exists in a rapidly changing world. Coral bleaching events remain a serious threat. Coastal development continues to put pressure on water quality. Illegal take still requires vigilance. And marine heatwaves, once rare, are now increasingly part of Hawaiʻi’s summer pattern.

The recovery at Kaʻūpūlehu doesn’t mean the reef is safe forever. It means the reef has been given a fighting chance.

A Lesson with Wider Meaning

Around the world, communities are wrestling with how to balance subsistence, culture, economies, and ecological limits. The story unfolding in Kaʻūpūlehu offers a compelling, grounded reminder: rest is not surrender. Rest is strategy.

In conservation, we often celebrate innovation, but sometimes resilience begins with restraint. Sometimes hope looks like patience, humility, and a shoreline left undisturbed. The community asked the ocean to wait—and in that waiting, abundance began to return. Now the question shifts: Can we care for what is recovering? Can we let stewardship guide us rather than scarcity or urgency?

Because in the end, this moratorium isn’t just about fishing. It’s about relationship. And hope—real, durable, evidence-based hope—is almost always relational.

Kaʻūpūlehu reminds us that the ocean is capable of recovery, if we’re willing to give it space, time, and respect. Sometimes the most powerful action isn’t doing more. Sometimes it’s pausing, and trusting that life remembers how to come back.

Comments